Following the Breadcrumbs

If you’re reading this, welcome! I’m glad you’re here. Perhaps you have been on a similar journey, or feel at a dead end, or restless not knowing what to do or where to go next.

I seem to find my way by following breadcrumbs, not by blazing neon signs. How about you?

It’s hardest for me to follow when the way is dark, when the crumbs are difficult to find, or when I feel lost. Rejection, wrong turns, and loss, ironically, help me eventually to see and follow my path. Patience and paying attention have all helped me to TRUST and to move forward.

One day, years ago now, while taking a break from studio work, I walked through the campus of the University of Minnesota to visit the Weisman Art Museum, as I often did. As I wandered through the galleries, I walked into a field of vibrating energy sparking from a large painting on the wall, the colors alive and shimmering, the movement of the brush strokes and paint pulling me through the painting into another place, another world, another time. My eyes welled, my body electrified. I stayed in its power long before I looked for the artist’s name.

Elizabeth Erickson; I will remember.

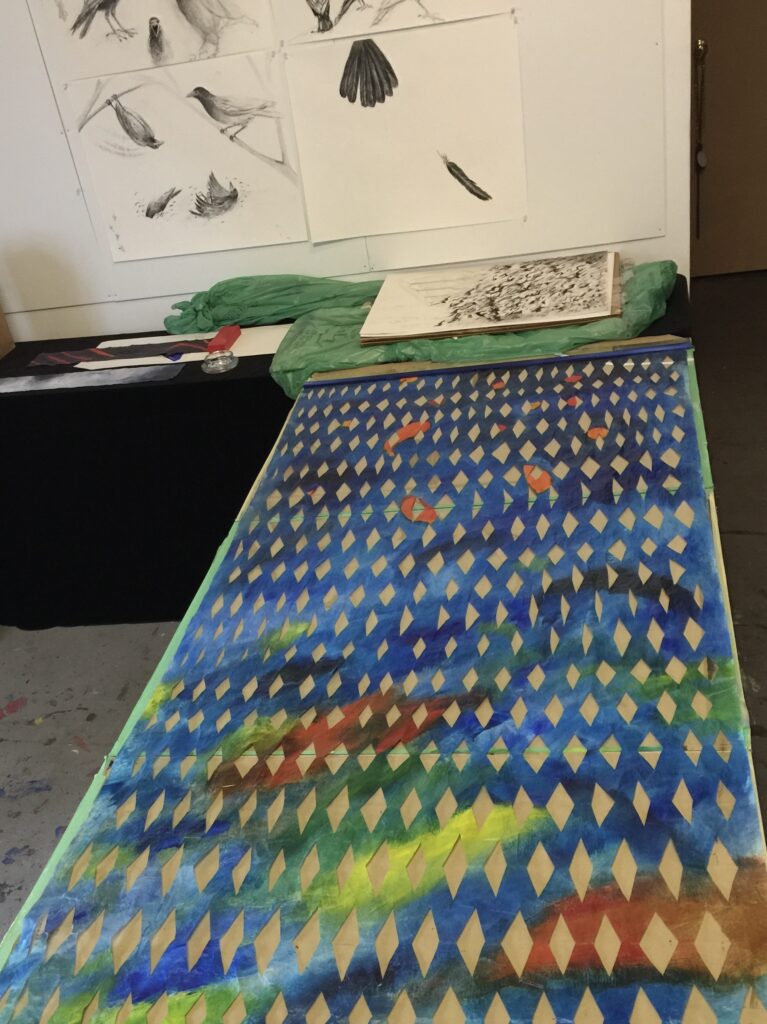

This is not the painting I saw at the Weisman Museum, but is another one from her body of work.

Sometime after that experience, I read about an opportunity at the Grand Marais Art Colony on the North Shore of Lake Superior: Women’s Art Intensive Studio Retreat sponsored by the Minneapolis College of Art and Design. Who was leading the retreat?

Elizabeth Erickson. I registered.

Kind friends offered their cabin for a place to stay.

When the time came to journey to Grand Marais on the North Shore, I didn’t bring any work-in-progress, only my supplies, materials, and sketchbook; I was open, looking, and ready for something new. Lake Superior had always spoken to me—the rocky shore, the sky, the ever-changing moody water. A fresh water sea.

Ten women artists settled into the art making space, originally a white clapboard church in the lake town of Grand Marais. Elizabeth Erickson, then a professor at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design, not only was a painter but also a poet and writer. We gathered in a circle; she asked questions like: “What is your original landscape?” We wrote. Shared. Elizabeth dismissed us. “Go. Draw. Pay attention. Work,” she said.

I packed my sketchbook and headed down to the rocky shore of the lake, a few blocks away. I drank in the brisk spring air, the scent of fresh pine and budding trees, and the view of the mighty lake stretching and filling the horizon line. I crossed the highway and walked along a path aiming for a certain rough and rocky shore I loved, the place where billion-year-old rock intersects with the water and sky. I never made it to that shore. Instead, I veered off, following a path near the Folk Art School and came into a clearing. The ground grabbed my feet. I stopped and stared.

Held upright on the land by four chicken-footed stands was a worn and weary fishing boat, certainly an antique. The entire wooden boat had been painted bone white, shimmering in its restoration under an open, protective structure. The beauty of the bow called to me. It was almost a butterfly. The boat and protective structure were alive.

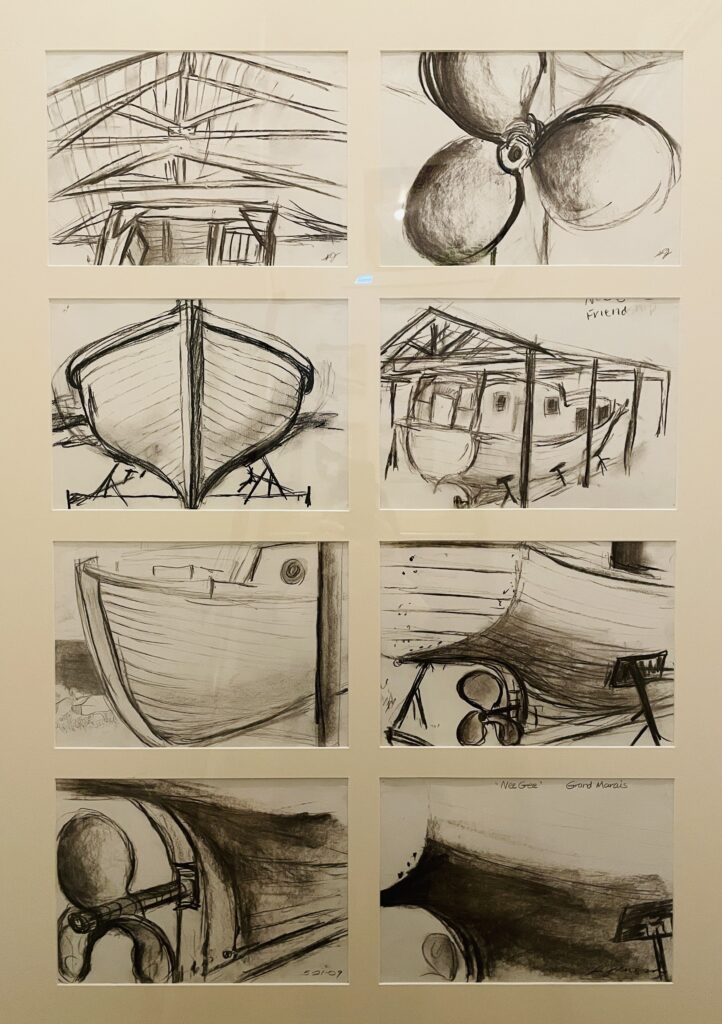

My sketchbook flipped open, hand and charcoal began drawing quickly what was before me: the magnificent bow, propeller in the rear, the chicken-footed stands, the cabin, and the mysterious relationship to the protective canopy and land, my heart beating a little faster. There was no planning, judging, or reviewing—only reacting and recording. I drew walking around the boat, studying every angle, learning as much as I could about the old fishing vessel on dry land under the canopy structure.

What was it about this relationship?

I walked and drew, finally coming to a rough painted sign, worn by the weather:

I took my sketches back to the Grand Marias studio and began an oil pastel drawing of Nee Gee.

The relationship between the boat and the canopy intrigued, moved and pulled me.

In my imagination, the propeller caught on fire, burning and turning with power.

In perfect unison, the boat and canopy lifted into the sky, free of gravity, moving as one, the structure never leaving the fragile boat. I painted one image after another, including

large images on glassine to be suspended in the air. But how would they hang? I had no suitable materials with me. I took a break to wander along the lakeshore. There, washed up on rock were cedar shakes, grayed and dried. I hauled them back to the studio—measured, cut, constructed, and painted the pieces to resemble the protective canopy structure over Nee Gee. The cedar shakes worked.

We ten women displayed our work on the last day of the transformative, week-long retreat. Painter/Poet/Professor Elizabeth Erickson gently probed and pushed us into greater depths and truth. I’m grateful for her guidance. I learned that Elizabeth passed away in 2024. Her contributions of artistry, teaching, and spirit will remain significant. For me personally, she said at our meeting: You can do anything you want to do. Those words still ring in my ears.

When I returned to Minneapolis, the experience of Nee Gee remained alive in my imagination—so alive that I needed to build a boat, something that merged the relationship of a boat being restored under its protective canopy. How could I possibly do that?

Elizabeth’s words whispered to me: You can do anything you want to do.

I let the idea take root and grow. Balsa wood came to mind for its lightness and flexibility. I’d worked with it before. How could the strips hold together? I didn’t want to use any nails, glue, or adhesives. Early one morning, between waking and dream, a image of a hole punch appeared. A hole punch? ! I had one in a drawer, got it out and gave it a whirl. It worked, easily creating the openings needed to secure the pieces together with twine. The boat and the protective canopy were becoming one.

Upon completion the boat was suspended, floating above gravity and within grace. The paint held the land, water, sky, and stars as the structure journeyed to unlikely places.

Still, the boat was not quite finished; it seemed to call for something more.

I painted and cut. A net appeared. What was the net to gather and hold?

Later, the net alone journeyed to a children’s hospital network, an art community, then finally to the healing space of an energy practitioner, to a place where I am healing.

I was compelled to make more nets, large and small, lifted as well as hung. I realized too that writing is net-making, linking one word with another, connecting us and our stories together. We all are netted together in one enormous weaving that spans time and space. We are caught in the net of story, not as prisoners, but as makers, as family, as fellow travelers, as receivers. It is our heart that we must follow, our heart that scatters the breadcrumbs through whisperings and nudges, through both sunshine and storm.

My life, and yours, are part of this net of creation, a net I need to help me to trust, to have courage, to know that I am knitted into something far greater than I can imagine. For me, this is true, even when we are shattered—especially when we are shattered. As of this writing, our community is grappling with the shooting that occurred August 27 at Annunciation Church and School, killing two children and injuring 15 children and three seniors. We struggle. We question. We keep caring, working, and making. Mattering to me is this “something far greater” that some call Spirit, the Universe, God, Love. And in Paul Tillich’s mysterious words: “the ground of all being.” Finding the breadcrumbs, one small piece at a time, is my heart, your heart, saying we must follow, we must make and tell our stories as we hold on to one another.

For me, following the breadcrumbs of my heart leads me to renewal and healing, to receiving, to community, and to purpose.

Thank you for reading all the way to the end. Thank you for the life you are leading, the path you are following, for the gifts you are sharing.